PROTEIN

Maintaining lean body mass can impact longevity. Optimal body condition, together with sustained lean body mass, is important for overall health.1-3

Lean body mass (LBM) includes skeletal muscle and organs, essentially everything except fat. It serves as an amino acid reservoir from which dogs and cats can build the proteins that are essential components of every cell, including immune cells, red blood cells and hormones.

With age, protein degradation often exceeds synthesis and this imbalance leads to progressive loss of LBM. This age-related loss of LBM, unrelated to disease, is called sarcopenia.

Sarcopenia in dogs and cats (and people) is associated with increased risk for mortality and other health problems.4

The science behind maintaining lean body mass

Keeping LBM loss to a minimum can help cats and dogs better maintain health, and potentially live longer.

Insufficient dietary protein may contribute to loss of LBM. Further, inadequate protein intake and loss of LBM can compromise a pet’s immune system, leaving them at greater risk from infections and other stresses.5

Historically, adequate protein requirements for dogs and cats have been calculated based on the amount of protein needed to maintain nitrogen balance. Yet multiple studies show that higher amounts of dietary protein are needed to maintain LBM.6-9

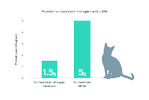

While cats need only 1.5 grams of protein per kilogram body weight to maintain nitrogen balance (protein) they need over 5g protein/kg body weight to maintain LBM.6

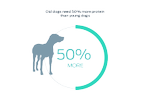

Dogs also require about three times more protein to maintain protein/DNA ratios (an indicator of protein reserves) compared to that needed to maintain nitrogen balance, and old dogs need 50% more protein than young dogs regardless of the measure used.8

Purina's research

Preserving lean body mass in aging

At all stages of life, maintaining ideal body weight is key to maintaining LBM. However, Purina studies show that cats commonly lose body weight and LBM after about 12 years of age. In some aging cats, this loss of weight and LBM leads to what may be referred to as the “skinny old cat syndrome.” Although nutrition cannot completely prevent sarcopenia in aging cats (or dogs), nutrition can play a role in delaying some of the age-related changes in body weight and body composition of these older felines.1

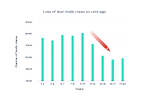

A cross-sectional study of 256 cats showed they begin to lose both LBM and fat at approximately 12 years of age.1,9

This progressive loss of LBM, called sarcopenia, poses a risk for health problems and a shorter life span.

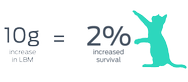

A longitudinal study of aging, non-obese cats, showed that every 10-gram increase in LBM resulted in a 2% increased chance of survival.1,10

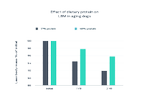

Purina research also demonstrated that older dogs fed a high-protein diet showed slower age-related loss of LBM than dogs fed a diet lower in protein.11

Preserving lean body mass during weight loss

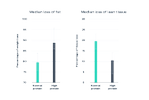

High-protein, low-calorie diets significantly increased fat loss and reduced loss of LBM in overweight cats undergoing weight loss when compared with cats fed normal protein, low-calorie diets.12

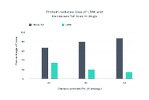

Purina research with overweight dogs showed that a high protein diet helps protect LBM during weight loss.13

In this study, overweight dogs fed a diet with a higher percentage of calories from protein lost more fat and retained more LBM while moving closer to their optimal body condition.

Loss of LBM during weight loss is common, but undesirable. Since lean body mass burns more calories than fat tissue, preserving LBM may help to prevent future weight gain.

Learn why a Body Condition Score is crucial in assessing a pet’s health.

Body composition and LBM are much better indicators of overall health in dogs and cats than body weight.13,14

A body condition score assessment is a focused, hands-on examination that veterinarians can use to evaluate the body composition of dogs and cats. Owners can also be taught the same method to monitor their pets.

Purina scientists developed and validated the 9-point Body Condition Score system (BCS) for cats and dogs, which is a simple method for estimating body fat and determining a pet’s optimal body condition, regardless of breed or body weight.14,15

Independently validated and published in peer-reviewed journals,16-18 this practical tool to support nutritional management for dogs and cats is now used by veterinarians worldwide.

In addition to assessing body condition, which primarily evaluates body fat, a separate evaluation of muscle mass is also important. The 4-point muscle condition scoring system (normal, mild, moderate, or severe loss of muscle mass) can help account for losses of LBM that may occur even in overweight pets.19-21

Key things to remember

- Maintaining LBM in cats and dogs is important for longevity and overall health.

- Purina research showed that every 10-gram increase in LBM was associated with a 2% increased chance of survival for cats over 12 years of age.

- Insufficient dietary protein contributes to loss of LBM. Studies show that higher protein diets can help slow the loss of LBM in dogs and cats.

- Purina researchers developed the 9-point Body Condition Score system to provide a practical tool to support nutritional management for dogs and cats. This method has been independently validated and is used by veterinarians worldwide.

Explore how nutrition can help pets lead better, longer lives:

Find out more

- Cupp, C. J., Kerr, W.W., Jean-Philippe, C., Patil, A. R., & Perez-Camargo, G. (2008). The role of nutritional interventions in the longevity and maintenance of long-term health in aging cats. International Journal of Applied Research in Veterinary Medicine, 6(2), 69-81.

- Kealy, R. D., Lawler, D. F., Ballam, J. M., Mantz, S. L., Biery, D. N., Greeley, E. H., Lust, G., Segre, M., Smith, G. K., & Stowe, H. D. (2002). Effects of diet restriction on life span and age-related changes in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 220(9), 1315–1320.

- Penell, J. C., Morgan, D. M., Watson, P., Carmichael, S., & Adams, V. J. (2019). Body weight at 10 years of age and change in body composition between 8 and 10 years of age were related to survival in a longitudinal study of 39 Labrador retriever dogs. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 61(1), 42.

- Freeman, L. M. (2012). Cachexia and sarcopenia: Emerging syndromes of importance in dogs and cats. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 26, 3-17.

- Datz, C. A. (2010). Noninfectious causes of immunosuppression in dogs and cats. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice, 40(3), 459–467.

- Laflamme, D. P. (2013). Protein requirements of aging cats based on preservation of lean body mass. Proceedings of the 13th Annual AAVN Symposium, (17). Washington, USA.

- Laflamme, D. P., & Hannah, S. S. (2013). Discrepancy between use of lean body mass or nitrogen balance to determine protein requirements for adult cats. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 15(8), 691–697.

- Wannemacher, R.W., & McCoy, J.R. (1966). Determination of optimal dietary protein requirements of young and old dogs. Journal of Nutrition, 88(1), 66-74.

- Perez-Camargo, G., Patil, A. R., & Cupp, C. J. (2004). Body composition changes in aging cats. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian, 26(Suppl 2A), 71.

- Cupp, C. J., & Kerr, W.W. (2010). Effect of diet and body composition on life span in aging cats. (2010). Nestlé Purina Companion Animal Nutrition Summit (36-42). Florida, USA.

- Kealy, R. D. (1999). Factors Influencing Lean Body Mass in Aging Dogs. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian, 2(11K), 34-37.

- Laflamme, D.P., & Hannah, S.S. (2005). Increased dietary protein promotes fat loss and reduces loss of lean body mass during weight loss in cats. International Journal of Applied Research in Veterinary Medicine, 3(2), 62-68.

- Hannah, S.S. & Laflamme, D.P. (1998). Increased dietary protein spares lean body mass during weight loss in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 12, 224.

- Laflamme, D.P. (1997). Development and validation of a Body Condition Score System for Cats: A clinical tool. Feline Practice, 25, 13-18.

- Laflamme, D.P. (1997). Development and validation of a Body Condition Score System for Dogs. Canine Practice, 22(4), 10-15.

- Bjornvad, C.R., Nielsen, D.H., & Armstrong, P.J. (2011). Evaluation of a nine-point body condition scoring system in physically inactive pet cats. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 72(4), 433-437.

- German, A.J., Holden, S.L., Moxham, G.L., Holmes, K.L., Hacket, R.M., & Rawlings, J. M. (2006). A simple, reliable tool for owners to assess the body condition of their dog or cat. Journal of Nutrition, 136(7), 2031S-2033S.

- Mawby, D.I., Bartges, J.W., D'Avignon, A., Laflamme, D.P., Moyers, T.D., & Cottrell, T. (2004). Comparison of various methods for estimating body fat in dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 40(2), 109-114.

- Freeman, L. M., Sutherland-Smith, J., Cummings, C., & Rush, J. E. (2018). Evaluation of a quantitatively derived value for assessment of muscle mass in clinically normal cats. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 79(11), 1188–1192.

- Freeman, L. M., Michel, K. E., Zanghi, B. M., Vester Boler, B. M., & Fages, J. (2019). Evaluation of the use of muscle condition score and ultrasonographic measurements for assessment of muscle mass in dogs. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 80(6), 595–600.

- Michel, K. E., Anderson, W., Cupp, C., & Laflamme, D. P. (2011). Correlation of a feline muscle mass score with body composition determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. The British Journal of Nutrition, 106 (Suppl 1), S57–S59.