PREBIOTICS

Prebiotics are non-digestible dietary carbohydrates such as fiber and resistant starch that serve as ‘food’ for the beneficial gut bacteria.1

The formal definition of a prebiotic is "a selectively fermented ingredient that allows specific changes, both in the composition and/or activity in the gastrointestinal microflora that confers benefits on host well-being and health."2 The ultimate aim of prebiotic supplementation is the enhancement of the gut microbiota: however, prebiotics have beneficial effects of their own, including improving the health of the gut itself.

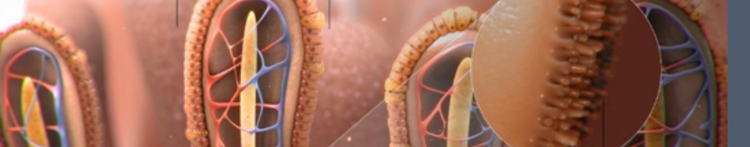

INTESTINAL MICROVILLI

Characteristics of prebiotics

All known prebiotics are fermentable, non-digestible carbohydrates. Prebiotics allow specific changes, both in the composition and/or activity of the gut microflora, that confer benefits upon host well-being and health.

To be a prebiotic, a food ingredient must:

- Resist digestion, absorption, and breakdown until reaching the colon

- Undergo fermentation by microbiota in the colon

- Selectively stimulate growth of only the beneficial bacteria.2

Purina uses purified inulin, wheat aleurone, and chicory root as prebiotics.

Inulin is extracted from chicory root using a hot water process and by further processing, oligofructose is formed. Naturally high concentrations of inulin can also be found in garlic, onion, artichokes and leeks.

Wheat aleurone is found as the single layer of cells between the bran and endosperm of the wheat grain.

The science behind prebiotics

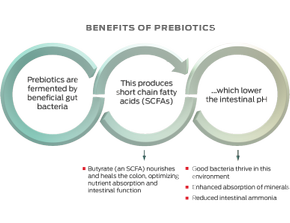

Dogs and cats lack the enzymes required to break down the chemical bonds of prebiotic ingredients like inulin and oligofructose. However, the microbiota in pets’ colons do have the ability to break these bonds via fermentation. This produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which lower the intestinal pH.

This lowered pH is responsible for many of the beneficial health effects of prebiotics. The acidic environment is unfavorable for the growth of pathogenic bacteria, and also enhances the absorption of minerals from the food that pets eat. Also in this acidic environment, potentially harmful ammonia from protein digestion is converted to ammonium ions that are excreted immediately instead of being absorbed for detoxification in the liver and then excreted in the urine as urea. This could play a helpful role in pets with decreased liver or renal function.3–5

SCFAs also have direct beneficial effects on the cells of the gut itself:

- Butyrate is the main energy source for colonocytes. It nourishes the colon and results in increased thickness of the intestinal mucosa, increased height of the villi, and improved crypt depth6,7

- This increased gut surface area improves nutrient absorption

- Butyrate has anti-carcinogenic and anti-inflammatory properties and can improve colonic healing in people,with inflammatory bowel disease and ulcerative colitis.8

Purina's research

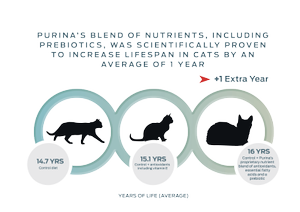

In a 9-year study, 77% of cats fed prebiotics from chicory showed either an increase in bifidobacteria and lactobacilli (beneficial types of bacteria), and/or decreases in Clostridium perfringens (potentially pathogenic bacteria).15 In the same study, cats that were fed a specific blend of nutrients that included a prebiotic lived an average of 1 year longer than cats fed a control diet.

Looking forward, prebiotics may be used as a tool to create a more controlled or ideal composition of intestinal microbiota, which could be correlated with specific physiological conditions in order to improve pet health.

Key things to remember

- Prebiotics are non-digestible carbohydrates that are fermented by beneficial bacteria in the gut.

- Purina has studied the beneficial effects of prebiotics such as chicory on gut health.

- Changes resulting from fermentation, such as the reduction of gut pH and the production of SCFAs, promote gut health.

- In the future, prebiotics could be used as a tool to create more favorable compositions of gut microbiota.

Find out more

1. Valcheva, R., & Dieleman, L. A. (2016). Prebiotics: Definition and protective mechanisms. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 30, 27–37.

2. Roberfroid, M. (2007). Prebiotics: The concept revisited. Journal of Nutrition, 173(3) Suppl. 2, 830S–837S.

3. Pinna, C., & Biagi, G. (2014). The utilization of prebiotics and synbiotics in dogs. Italian Journal of Animal Science, 13, 169–178.

4. Hesta, M., Janssens, G. P., Debraekeleer, J., & De Wilde, R. (2001). The effect of oligofructose and inulin on faecal characteristics and nutrient digestibility in healthy cats. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition (Berl), 85, 135–141.

5. Younes, H., Garleb, K., Behr, S., Rémésy, C., & Demigné, C. (1995). Fermentable fibers or oligosaccharides reduce urinary nitrogen excretion by increasing urea disposal in the rat cecum. Journal of Nutrition, 125, 1010–1016.

6. Buddington, R. K., & Sunvold, G. D. (1998). Fermentable fiber and the gastrointestinal tract ecosystem. Recent Advances in Canine and Feline Nutrition: 1998 Iams Nutrition Symposium Proceedings, pp. 449–461.

7. National Research Council (2006). Energy. In: Nutrient Requirements of Dogs and Cats. pp. 28–48. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

8. Knudsen, K., Serena, A., Canibe, N., & Juntunen, K. (2003). New insights into butyrate metabolism. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 62, 81–86.

9. Patil, A. R., Czarnecki-Maulden, G., & Dowling, K. E. (2000). Effect of advances in age on fecal microflora of cats. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Journal, 14(4), A488.

10. Patil, A. R., Carrion, P. A., & Holmes, A. K. (2001). Effect of chicory supplementation on fecal microflora of cats. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Journal, 15(4), A288.

11. Czarnecki-Maulden, G. L. (2001). Microflora and fiber in the GI tract: Helping the good guys. Veterinary Forum, 18(9), 43–45.

12. Czarnecki-Maulden, G. (2000). The use of prebiotics in prepared pet food. Veterinary International, 2(1), 19–23.

13. Czarnecki-Maulden, G. L., & Russell, T. J. (2000a). Effect of chicory on fecal microflora in dogs fed soy-containing or soy-free diets. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Journal, 14(4), A488.

14. Czarnecki-Maulden, G. L., & Russell, T. J. (2000b). Effect of diet type on fecal microflora in dogs. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Journal, 14(4), A488.

15. Cupp, C. J., Kerr, W. W., Jean-Phillipe, C., Patil, A. R., & Perez-Camargo, G. (2008). The role of nutritional interventions in the longevity and maintenance of long-term health in aging cats. International Journal of Applied Research in Veterinary Medicine, 6, 69–81.