INTESTINAL VILLI WITH BACTERIA

The Gut-Brain Axis

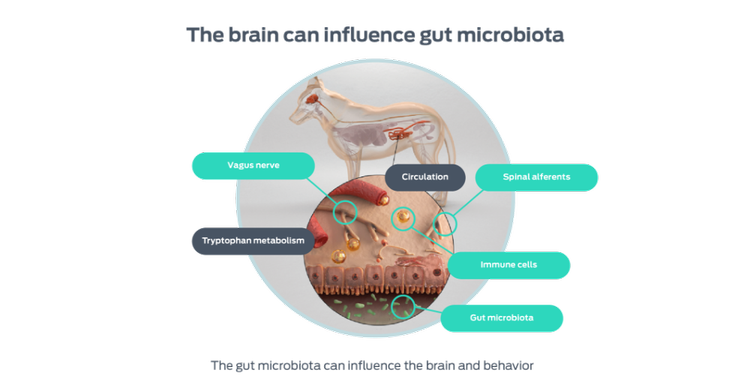

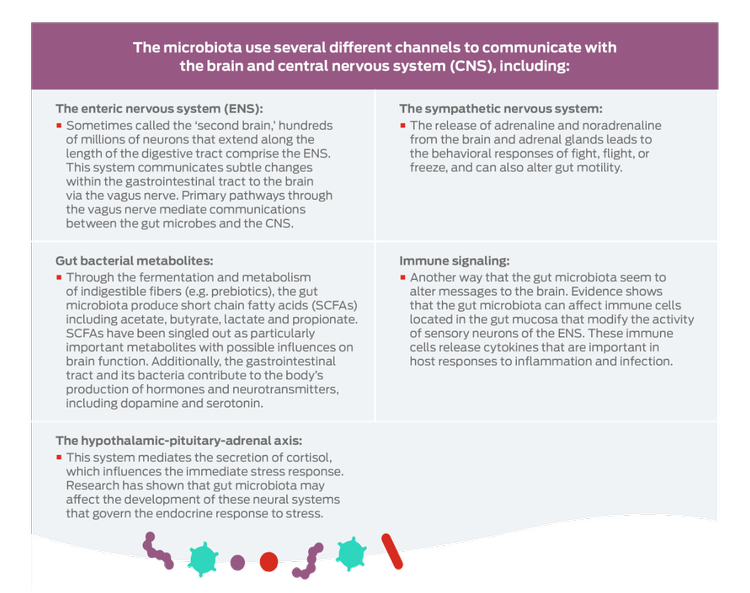

The term 'gut-brain axis' refers to the constant bidirectional communication between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain.

The idea that the gut influences the brain, and therefore also behavior, is widely understood and accepted. The concept has made its way into everyday language with terms such as 'gut feeling,' 'gutsy' and 'butterflies in the stomach.' Despite this, scientists have only recently begun to unravel the mechanisms behind the gut-brain axis. This communication link is at the core of an emerging area of research – neurogastroenterology.

Mounting evidence suggests that gut microbes help shape normal neural development, brain biochemistry and behavior.1 In particular, the gut microbiota are emerging as a key node in the communication between gut and brain. This has led to the coining of a new term: microbiota-gut-brain axis.

MICROVILLI AND BACTERIA

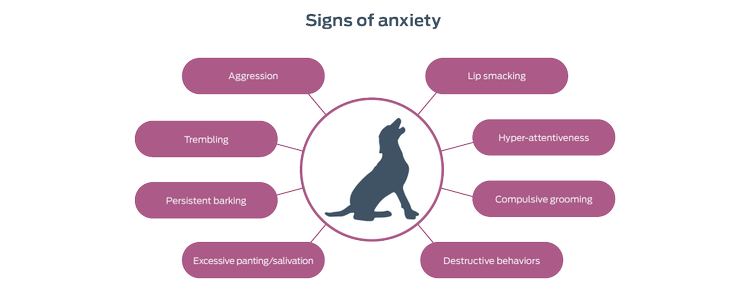

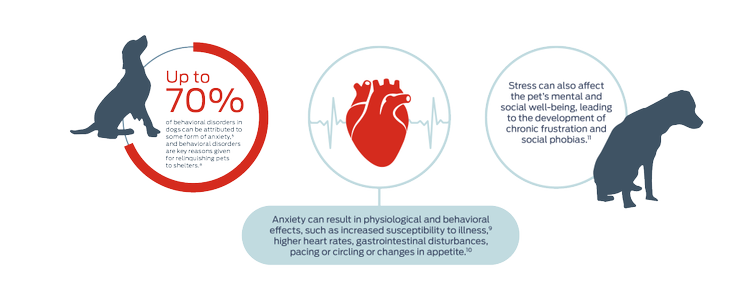

Research has shown many links between gut bacteria and conditions such as obesity, Alzheimer’s disease and pet anxiety.2-4 The latter is important because up to 70% of behavioral disorders in dogs can be attributed to some form of anxiety.5

The role of the veterinary general practitioner in identifying and treating their patients’ behavior problems – such as anxiety – is a crucial one.6

Pet owners may not recognize all signs of fear and anxiety, or may only reach out once the problem has escalated to the point of crisis.7

Consequences of Anxiety

Purina's research

In a blinded, crossover study, Purina scientists discovered that dogs supplemented with a specific strain of Bifidobacterium longum (BL999) showed significant reductions in several anxious behaviors when compared to placebo. A majority of the dogs supplemented with BL999 showed lower heart rates and salivary cortisol levels. From behavioral and physiological perspectives, B. longum BL999 had anxiety-reducing effects on anxious dogs.

Purina Institute’s Meet the Scientist Video Series

Explore other areas of the Microbiome Forum

Find out more

- Shen, H. H. (2015). Microbes on the Mind. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(30), 9143–9145. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509590112

- Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2017). Gut–brain axis in 2016: Gut-brain axis in 2016: Brain-gut-microbiota axis - mood, metabolism and behaviour. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 14(2), 69–70. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.200

- Köhler, C. A., Maes, M., Slyepchenko, A., Berk, M., Solmi, M., Lanctot, K. L., & Carvalho, A. F. (2016). The gut-brain axis, including the microbiome, leaky gut and bacterial translocation: Mechanisms and pathophysiological role in Alzheimer’s disease. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 22(40), 1–15. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160907093807

- McGowan, R. T. S., Barnett, H. R., Czarnecki-Maulden, G. L., Si, X., Perez-Camargo, G., & Martin, F. (2018, July). Tapping into those ‘gut feelings’: Impact of BL999 (Bifidobacterium longum) on anxiety in dogs. Veterinary Behavior Symposium Proceedings, Denver, CO, pp. 8–9.

- Beata, C., Beaumont-Graff, E., Diaz, C. Marion, M., Massal, N., Marlois, N., Muller, G., & Lefranc, C. (2007). Effects of alpha-casozepine (Zylkene) versus selegiline hydrochloride (Selgian, Anipryl) on anxiety disorders in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 2, 175–183.

- Stelow, E. (2018). Diagnosing behavior problems: A guide for practitioners. Veterinary Clinics of North America, 48(3), 339–350. doi:10.1016/ j.cvsm.2017.12.003

- Ballantyne, K. C. (2018). Separation, confinement, or noises: what is scaring that dog? Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 48(3), 367–386. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.20112.005

- Salman, M. D., Hutchison, J., Ruch-Gallie, R., Kogan, L., New, J. C., Kass, P. H., & Scarlett, J. M. (2000). Behavioral reasons for relinquishment of shelter dogs and cats to 12 shelters. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 3(2), 93–106.

- Tanaka, A., Wagner, D. C., Kass, P. H., & Hurley, K. F.. (2012). Associations among weight loss, stress, and upper respiratory tract infection in shelter cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 240(5), 570–576. doi: 10.2460/javma.240.5.570

- Landsberg, G., Hunthausen, W., & Ackerman, L. (2013). Behavior Problems of the Dog & Cat. Great Britain: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 181–182.

- Mills, D., Karagiannis, C., & Zulch, H. (2014). Stress – Its effects on health and behavior: A guide for practitioners. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 44, 525–541.

- Mariti, C., Gazzano, A., Moore, J. L., Baragli, P., Chelli, L., & Sighieri, C. (2012). Perception of dogs’ stress by their owners. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 7(4), 213–219.

- Seibert, L. M., & Landsberg, G. M. (2008). Diagnosis and management of patients presenting with behavior problems. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 38, 937–950.

- Patronek, G. J., & Dodman, N. H. (1999). Attitudes, procedures, and delivery of behavior services by veterinarians in small animal practice. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 215(11), 1606–1611.